Taken from “10 Secrets To Empowering Teen Leaders,” this one demands you take them seriously. Once you do that, you’ll get only their best work

I’ve been reflecting lately. How does a teacher empower young people to grow into leaders? I don’t believe it happens by accident.

Perhaps I’ve been thinking about it because I am in the midst of making a major change in my life. I’m moving from Vashon Island High School in Washington state, where I’ve spent the last six years building a journalism program, to Stafford High School in Virginia, where I have been asked to advise another journalism program.

My goal is to build the same type of student leadership program I’ve fostered at Vashon. Why not figure out what works in this program so I can replicate it at Stafford?

So I’ve spent the last few weeks unpacking the principles I follow to empower student leaders.

I’ve used these principles since 1989, when I earned my degree and began working with young people. I’ve applied these principles while directing drama, advising yearbook and newspaper staff, and running a student store.

In each organization, I eventually realized I had one goal in mind: empowering young people to become leaders. In other words, I was offering them principles that would help them in their eventual vocations.

It must work. Across the years, multiple students have come back to tell me the skills they learned from me were skills they are currently using in the real world.

For example, one of my finest editors is now a pediatrician. Another is an entrepreneur who has started a series of successful companies. Some have gone on to become real journalists. One even produces shows on Broadway.

Students have told me that they don’t learn these skills anywhere else in school. So I thought perhaps I should codify and share what I do. Other educators may find it helpful.

Over the next ten weeks, I’ll be sharing these secrets, one per week, telling you stories about how I learned them the hard way.

If these make sense to you, I urge you to share in the comments about how these principles have worked for you — or haven’t.

Once I’m done, I’ll turn this series of blogs into an online book. If you offer a comment that makes us all think, I’ll offer you a free copy.

And so without further ado, here we go.

Secret #1. Take your students’ ideas seriously: real leaders believe their ideas matter

I remember when my perspective on this changed.

I was judging newspapers for National Scholastic Press Association six years ago, just as I was stepping into the role of newspaper adviser — the job I’m currently leaving. I received three different sets of papers to evaluate.

How do you let high school kids make the final decisions about what stories should run? How do you trust them? What if they take advantage of their freedom? What if they make mistakes?

One of them in particular caught my eye. The stories were amazing, the coverage was broad and mature, and the photos and design positively brilliant. It looked like a professional paper. The other two looked like … high school papers. Yet all three were published by high schools.

“What is the difference?” I asked myself.

I looked at the notes offered by the staff’s adviser, and then looked again. She explained that the editors made all decisions regarding the paper. No articles were approved by her before they went to press. The students were the ultimate publishers.

This shocked me. I knew all the legends about yearbooks and newspapers where students raced out of control — where they published racist language or ran obscene photos.

How do you let high school kids make the final decisions about what stories should run? How do you trust them? What if they take advantage of their freedom? What if they make mistakes?

But as I leafed through edition after edition, I saw the evidence in front of me. These students took their work seriously. They were doing quality work.

It took me several years to process this (and I still don’t give my kids the same degree of freedom that amazing high school adviser does) but it changed the way I advise.

When I step in and change what my students have done, I am in essence telling them that my ideas are superior to theirs, and that they can’t be trusted to make decisions. There’s no better way to destroy motivation.

On the other hand, when I let student leaders make final decisions — when I listen to their ideas, give them my perspective, but emphasize that they are ultimately the ones who need to make the final decision — I tell them their ideas matter.

And when my student leaders begin to believe their ideas matter, they’ll gain self-confidence. Those who follow them will trust them because they trust themselves. This in turn will help them generate even better ideas. This creates a feedback cycle of momentum that is indispensable to success.

I’ve always wondered why students who go to private schools end up being the leaders in our nation.

Now to be clear, I am a committed public school teacher. I believe every student should have an equal chance to receive an education. But I also think private and independent and charter schools have lessons to teach us.

I remember thinking about this when teaching at a private school in Los Angeles. I watched the teachers teach, and concluded the teaching was no better there than it was at the Midwestern public high school where I had previously taught.

I still think about this. Why is their students’ rate of entry into Ivy League schools so much higher? Why do so many of our nation’s top leaders come out of private schools?

When I step in and change what my students have done, I am in essence telling them my ideas are superior to theirs, and they can’t be trusted to make decisions. There’s no better way to destroy motivation.

I decided it’s because the expectations are so utterly different. In other words, a student’s self-confidence and sense of self has everything to do with the quality of work they produce.

Students from wealthy backgrounds and nurturing homes are told from childhood how important they are.

For example, at The Archer School where I taught in Los Angeles, parents are still paying over $40,000 per year in tuition to send their child to school. That’s for seven years, Grades 6-12. This doesn’t count their previous elementary years, also at private schools.

Do the math — most parents in my Midwestern hometown don’t pay that much for their child’s entire college education.

My students in the City of Dreams may have had struggles with their parents, or they may have thought they weren’t getting enough attention at home, but the fact they were being sent to a private school with other important people — with children of the rich and the famous — confirmed to them they were special, important.

Their parents paid significantly to educate them. Their teachers — at the ratio of one teacher per eight students — gave them all the extra time they needed outside of class. Their administrators told them how important they were to the future leadership of our nation.

And by the time they graduated from high school, and were admitted to the nation’s top schools — thanks to the alumni connections of their guidance counselors and teachers — they believed it.

They believed they were part of the elite. They believed they weren’t just the average student.

And predictably, these students have now begun to claim leadership positions across every strata of society. None of this has surprised my former students. They were told from childhood that this is what would happen.

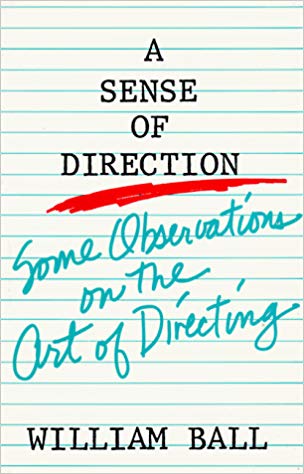

In A Sense of Direction: Some Thoughts on the Art of Directing, director William Ball argues that the way to get actors to produce their best work is to take seriously whatever ideas they come up with.

Watch them try something mediocre, affirm it, and then say, “Let’s try that again,” Ball instructs.

The little id within the actor — that part of us that comes up with ideas, and has always been told we’re useless — gapes in amazement and once more sends down a bad idea. “Take it seriously again,” Ball instructs.

At this point, the little id says, “You know what, this guy’s for real,” and from then on, you will get the actor’s best work.

I use the same method in working with young people.

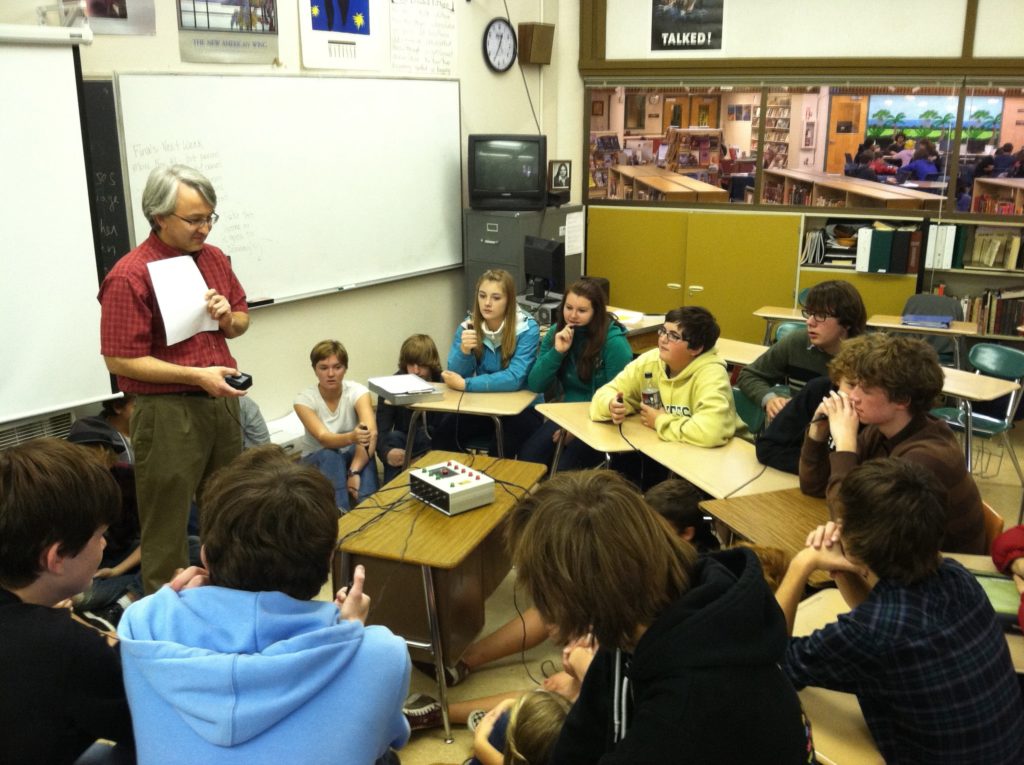

For example, in my newspaper program, I make a point of telling my staff that I am not permitted to decide on what content or stories they run. I am the adviser and the teacher: I am not the editor.

They are.

So the students must come up with the ideas themselves. In fact, I make a point of occasionally offering an idea, but praising them when they ignore my ideas. The ideas they come up with are better, I tell them. My job is to advise. Their job is to lead.

Watching new staff members figure this out is delightful. Somewhere around the second or third issue of the paper, they finally figure out I’m serious. I don’t run the paper. My editors do.

When I do offer a good idea, I make sure I let them know that they need to make the final decision. When teachers or community members come to me with story ideas, I say to them point-blank — and often in front of my students — that they need to talk to my editors, because my editors are the only ones who can make that decision.

When my editors see that I’m taking them seriously, when they see I’m treating them like adults — that little id within them decides it’s time to send down its best ideas.

That is the first secret to empowering teens: Take their ideas seriously. Once they believe you, they will have the freedom to own their ideas, and you’ll get only their best work.

Leave a Reply