Great teaching goes far beyond the teacher’s charisma. In fact, it’s not about the teacher at all— it’s about helping students learn.

I REMEMBER STANDING in line at the cafeteria of Catholic Central High School in Steubenville. It was late November 1991, and I had just begun to get comfortable teaching there. I loved giving lectures about literature, encouraging students to discuss the ideas they had discovered while reading.

Suddenly, the student across from me in the lunch line — I’ll call her “Sam” — spoke up.

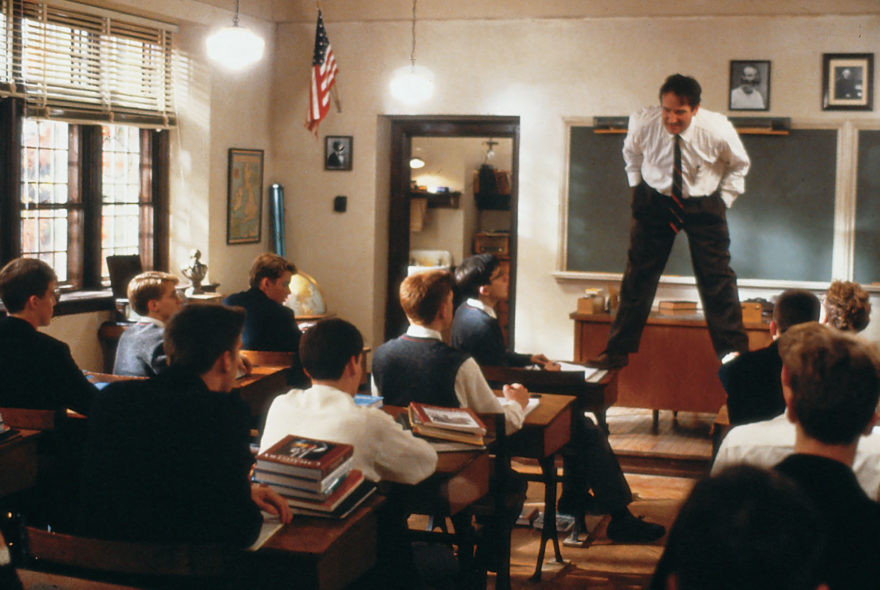

“Mr. Denlinger, has anyone told you that you remind us of Mr. Keating in Dead Poets Society? Your passion for literature is just incredible.”

I wasn’t surprised that Sam loved the film. She was a bohemian, she had once told me. Now she beamed up at me admiringly.

Like my student, I also loved the film. I had seen it five times in the theater the year it came out. I had taken other people to see the film. I held Mr. Keating in awe. He really knew how to connect with students.

Like Sam.

I tried to hold back the smile, but it broke loose anyway. I was downright flattered. The idea that students might compare me to him — my entire day, no, my entire year had just been made.

I made my way to the teacher’s lunchroom, my head buzzing with excitement.

What I couldn’t have known was this: comparing me to Mr. Keating was anything but a compliment.

THE LATE ROGER Ebert, whom I respect deeply as a film critic, hated the film. “It is, of course, inevitable,” writes Ebert, “that the brilliant teacher will eventually be fired from the school, and when his students stood on their desks to protest his dismissal, I was so moved, I wanted to throw up.”

Ebert believed teaching should be more than charisma and performance. It’s not about you — it’s about helping students learn.

For example, although Keating introduces his students to many poets, he doesn’t examine them “in a spirit that would lend respect to their language; [the poems are] simply plundered for slogans to exhort the students toward more personal freedom.”

Ebert’s point is clearly made after Keating’s firing, when the principal shows up to teach the class. Few students can recall what they learned.

When I first saw the film, I didn’t notice this. Today, after years of creating lesson plans, I’m inclined to agree with Ebert.

As a newspaper and yearbook adviser of 18 years, I hear everything. My experience tells me teaching is not a popularity contest. Students resent teachers who substitute a charming performance for real teaching.

Students want to learn. They may not express that during class — few students will deliberately ask for more work — but after the semester is over, they express nothing but scorn for a popular teacher who isn’t doing their job.

Students know who the “easy” teachers are, and they also know who they respect — the teacher who makes them learn.

Which is why, over the course of my career, I have slowly come to understand Ebert’s critique.

“At the end of a great teacher’s course in poetry,” Ebert writes, “the students would love poetry; at the end of this teacher’s semester, all they really love is the teacher.”

LAST WEEK, WHILE going through my files, I stumbled upon a speech I gave in 1991 to an education class. I titled it “Surviving the First Year of Teaching: Discovering the Flip Side of Dead Poets Society.”

In the speech, I spoke of Keating’s passion for literature, comparing him to experienced teachers who had become cynical and bitter. I hoped I wouldn’t take that route.

Today, I’m happy to report I haven’t. Perhaps that’s because I took a year’s sabbatical in 2007-08 to write full-time for HuffPost. Being away from the classroom rekindled my love for it. Today, I enjoy teaching high-school students even more than I did when I originally wrote that speech.

At the end of a great teacher’s course in poetry, the students would love poetry. At the end of this teacher’s semester, all they really love is the teacher.

Experience has its advantages. It imbues the teacher with strategies and skills that allow them to play the long game. It’s similar to a good marriage. Although the fireworks and passion of a new relationship is exciting, the stability of the familiar grounded in deep friendship can be more satisfying.

Mr. Keating did not survive teaching his first year at Welton Academy. Although we admire his flamboyant, authentic style, perhaps we can learn from his experiences, along with that of master teachers.

AS PART OF that speech I gave in 1991, I came up with 10 Rules for Surviving the Classroom. To offer a fresh perspective, I’ve flipped the rules. Here is what you should not do if you wish to survive as a teacher.

- Don’t bother finding out what your supervisor expects of you. Why worry about trying to please anyone but yourself? After all, the goal of an excellent teacher is to show how original you are. You know how much you hated those boring high school teachers you had (that’s why you entered the field, right? To show them how it’s really done?). And during conferences when your principal is trying to suggest ways to improve, why listen? He doesn’t know anything. If he did, he’d have remained in the classroom. So just smile and nod and then go with your gut. You can always just get another job if this one doesn’t work out. The world is desperate for great teachers like you.

- Wait to establish discipline until after your students like you. The line “Don’t smile ’til Christmas” was created by teachers who hate kids. After all, once the kids see how cool you are — what a rebel you are, just like them — they’ll gather around you in awe. Then you can dispense your original wisdom.

- Being on time is for losers. It’s okay to slip into class just as the bell rings. Or a little bit late. It worked in college, didn’t it? After all, your time outside of school (and your sleep) is valuable. Besides, it’s good for kids to have to wait for you. It shows them who’s really in charge.

- Make yourself the center of every class. That’s why they’re here, right? To see you perform. The classroom is a stage, and you are the star. You want students to worship you, hang on to your every word, even imitate you.

- Ignore deadlines. Most administrators won’t notice anyway, and you’ve got more important things to do than boring paperwork. When your supervisor complains or writes you up (like you care!), just give them an excuse.

- Make your students your closest friends— they’ll think you’re totally cool. You remember all those teachers who made you remember they were the adult? Remember how boring they were? Let your students know about all your romances, your breakups, the way you got trashed last night, the cool parties you attend. You want them to know you’re just like them.

- You’re not responsible to keep your room neat and orderly. That’s the janitor’s job, right? Besides, clutter is the de facto mark of a genius. So relax, encourage the kids to break the rules, let the clutter accumulate, and bask in your own brilliance. The kids will love you.

- Feel free to criticize and ridicule the people around you — your faculty colleagues, your administration, even national leaders who belong to the “wrong” political party. Why respect those in authority? You’re an original, and you want to connect with your students emotionally. Respect for authority is so “old people.” Authenticity is what you want. Once students see how brilliant your sarcastic takedowns are, they’ll follow you without question.

- Take advantage of your power as a teacher. You have the right to speak out — especially when parents disagree with and criticize you. If someone criticizes you, go after them in no uncertain terms. Twitter is good. Facebook is better: why not deal with the elephant in the room? This will teach parents to fear you, and whatever they’ve done, they won’t do it again.

- YOUR ACADEMIC CLASSES are boring — focus all your spare time on your coaching or advising. After all, kids get so bored learning academic stuff, but they really wake up after school when they play soccer or work with you in a theatrical production. So be sensible. Extracurriculars — that’s where you really want to put your time. Not in your lesson plans. Being a star coach or adviser will help the students see you as cool, like them, not like a boring adult who’s always demanding extra work on difficult homework.

Remember, these are the 10 rules you should not follow. (It’s easy to forget.)

UNFORTUNATELY, I’ve followed most of the above rules at one point or another in my teaching career. So next week in “‘Dead Poets Society’: Breaking down the rules” (Part 2), I’m going to reframe these 10 rules — and show how I learned each one the hard way.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you, from you teachers out there who would care to risk sharing from your own classroom screwups. Tell us a story. What is the one rule you learned teachers should not break?

In the process, we’ll discover together how the film really is a great soul teacher — perhaps in unexpected ways.

My teaching “screw-up” was in my first year of teaching a sixth grade class in a Christian school in the late 60’s. Periodically I would order educational movie films and even film strips to enhance the student’s learning experience. On this particular occasion, I had gotten a science film strip and was setting up the film strip projector and film and announced to the students that we were going to watch a “strip film”….. Fortunately none of the students seemed to have noticed my slip up (or they were too polite to make a point of it) and so I quickly moved on the the subject at hand.

Great piece! I think some of my most painful mistakes (both to me and to my students) came when I broke the rule of processing my emotions OUTSIDE of class. I let anger at some students build up, and, while I didn’t yell, I’m certain that I wasn’t properly in control of my emotions. I ignored the requirement that I always be the adult, even when it was inconvenient.

Okay, Devil’s Advocate from one who ADORES the movie: it is not all about Keating. He inspires the boys to love poetry and suck the marrow out of life. He inspires Neil to act. He inspires Todd to break through his shyness and create poetry. The movie should not be blamed because of the hammy/compelling Robin Williams. But Keating, as written, is the best of teaching, leaving his students inspired and loving life. There. My two cents. Great column!

In his memoir Teacher Man, Frank McCourt writes: “I was more than a teacher. And less. In the high school classroom you are a drill sergeant, a rabbi, a shoulder to cry on, a disciplinarian, a singer, a low-level scholar, a clerk, a referee, a clown, a dress-code enforcer, a conductor, an apologist, a philosopher, a collaborator, a tap dancer, a politician, a therapist, a fool, a traffic cop, a priest, a mother-father-brother-sister-uncle-aunt, a bookkeeper, a critic, a psychologist, the last straw” (p. 19).

During my 37 year career as a high school English teacher, I acted in the role of every single person on McCourt’s list, whether or not I wanted to be, and regardless of my qualifications. Filling all of those roles helps develop some genuine humility in a teacher and shapes him/her into being more of a servant on the side than a sage on the stage.

I, too, was once enamored by Mr. Keating, but Steven’s second look at the man, the myth, the (celluloid) legend, speaks Truth that unmasks Hollywood. I would add: “Carpe Diem,” which appeared on T-Shirts everywhere as a result of that 1989 film, is also a flawed concept to those of us who believe that this present life is not the only one we will ever live. (Think of Hamlet’s pondering of the “undiscovered country, from whose bourn no traveler returns.”)

I don’t think you can determine was makes an excellent teacher without first determining what makes excellent education. The shift toward loose, friendly teachers picked up steam as we lost sight of a classical Western curriculum and instead saw school as an arena for self-exploration. It cannot be both, just as a teachee cannot be both. He may appear to be, but one (the authority or the accomplice) will have the last say.

Thanks for this, Beth. I’m looking forward to your next blog: I know it’s in the works.

While I realize this is an older article, I just happen to be showing this film to my class this week, and it is also why I too became a teacher.

A couple of things. First, I think the film is made for younger people. They are inherently drawn to the teacher that breaks free from the monotony and shakes things up. It sells tickets. And, admittedly, in my third year as a teacher, I am guilty of breaking many of these rules, not always intentionally, and I am still learning. However, I think the movie is treated a bit unfairly.

First, the claims that Keating taught them nothing and ignored pedagogy is inaccurate. It is simply that the movie didn’t show us those things. As movies do, it only focused on the most entertaining of his lessons. I can’t imagine movie audiences would be riveted by a scene of Keating discussing iambic pentameter (though I’m sure Robin would have found a way). And, in the scene where Nolan asks where they are in the book and what they’ve learned, they cannot answer. However, if he had presented them with a poem to analyze, I’d wager they would be able to offer insightful opinions and interpretations. As I take my Masters classes, they emphasize to not teach the content, but to simply use the content to teach the lessons the teacher has chosen. This was not the nature of mainstream pedagogy in 1989, much less in the 50’s, which makes Keating a pioneer.

His focus was on critical thinking. And, while it certainly is important to know the content, there is little merit to simply memorizing facts and information, especially when it comes to literature.

My second point is that much was left out of the movie that answers many of the questions and short-comings many have claimed about the film. First, many of the scenes left out of the movie have him discussing the finer points of poetry, and there is even mention of how he will harshly grade the students’ essays, showing that he is concerned for their academics as well.

Perhaps the most important point left out or changed in the movie is that Keating is dying. His impending death greatly informs his emphasis on the boys sucking the marrow from life and seizing the day. It isn’t simply haphazard encouragement to be reckless and rebellious, but an informed point of view as he stares down his own mortality. This provides a deeper motivation for the character than is implied in the film.

I’m not saying Keating is without his faults. Certainly, I would never have a child defy their parents, and I often have to remind my students they are, in fact, children. I am a teacher today because of this movie, and the teacher who showed it to me, which was my own personal Mr(s). Keating. She opened my eyes to the power of literature and the necessity for seeing things differently. I believe there is still great merit in this film for analysis, and perhaps even for a little bit of inspiration and hope for future teachers.