It’s the belief that all of us are broken, that no timber is made straight, that life is intended to be a series of struggles and lessons — and that all of this builds moral fiber and strength of character.

I WAS SITTING in a job interview — at a small, independent school in Seattle — when the truth hit me, finally. It was July 2011. I had been teaching at their summer camp, and they’d invited me to interview for a full-time job.

I needed the work. I needed the salary. But I wasn’t sure I needed to teach high school. After all, I had spent the last three years writing for HuffPost, teaching night school, and trying to finish a memoir.

Now I wanted to get married, and I needed full-time work.

“So why do you want this job?” my interviewer asked me.

I looked at her for a moment. I didn’t think she’d want to hear my first response: that my wife had told me it wasn’t practical to teach part-time and work on a book that would never be ready to sell.

Nor did this interviewer want to hear what I had begun to suspect — that I was going through a midlife crisis and was scrambling to find my way back to firmer footing.

Out in the hallway, I heard the squeak of a bucket as the janitor squeezed out her mop and began another round on the already clean floor.

I remembered a conversation I’d had with a close friend two days earlier. “I’m a performer,” he told me, “because it’s the only thing I really know how to do.” And suddenly, there in that overstuffed office, I knew my answer.

It had been lurking in the background all the time as I’d put my resume together, struggled to articulate my teaching philosophy, and tried to figure out why it always came down to this — me across the desk from some administrator, confusedly trying to convince them that I was right for the job.

Now, I looked at my interviewer, who was waiting patiently, a kind smile on her face. And in a flash, the answer came to me.

“I want this job,” I said slowly, “because teaching is the most meaningful thing I know how to do.”

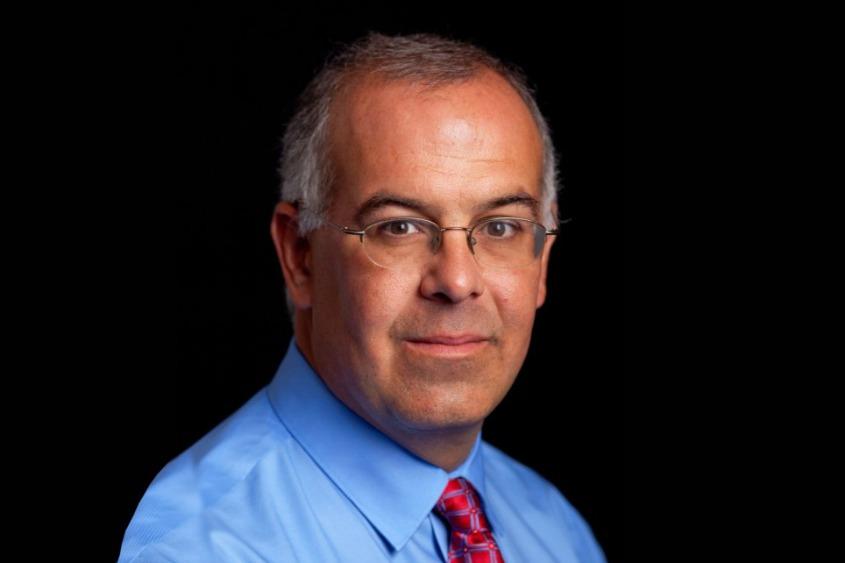

THREE YEARS AFTER that fateful interview, I picked up David Brooks’ amazing book, The Road to Character. Or rather, listened to it on my iPhone as I stripped blackberry bushes in the pasture below our lawn, clearing the view. The ground was muddy, the brambles sharp and stubborn. I was inspired, moved to tears by Brooks’ stories, lifted beyond my own expectations for myself.

It’s that sort of a book.

I had been reading Brooks for years. I like the viewpoint he brings to the New York Times columns — a moderate viewpoint that satisfies the Blue Dog Democrat within me. But there had never been anything particularly moral about his writing.

So imagine my surprise upon reading The Road to Character, the epistle that springs from America’s stoic, Yankee roots. It’s all about morality.

“I want this job,” I said slowly, “because teaching is the most meaningful thing I know how to do.”

Building a moral character.

Brooks argues that we need to return to an earlier way of shaping character. Something’s been lost in the last century. We need a more traditional definition of sin as a part of our “moral vocabulary” — the word “sin” shouldn’t be a light-hearted reference to the eating of fattening desserts.

As the poet says, life is real and life is earnest.

How can you improve your moral character if you don’t know where you’ve transgressed in the first place?

Sounds like orthodox Christianity. Perhaps that’s because of Brooks’ primary and secondary education. In an interview with The Times of Israel, Brooks said:

“The school that probably had the biggest influence on me was called Grace Church School,” he added. “I was in the choir, and so I sat in chapel every day. Then I went to an Episcopal camp for 15 years, and then I read Reinhold Niebuhr, and then I fell in love with St. Augustine, and somehow you find that story settling into you. And so I feel more Jewish and more attached to the Christian story than ever. Both.”

In The Road to Character, Brooks embraces the core tenants of his early education.

After laying down his basic philosophy in his introduction — modern Americans have lost touch with aspirational character values, focusing on “resume values” that help us get ahead rather than “eulogy values” that last beyond your life — Brooks relates the life stories of 10 historical figures.

Each of them models a moral quality he believes Americans have abandoned.

Brooks’ ability to parse a character’s life, identifying the traits he himself struggles to master, serves him well in this book. When I listen to him tell stories, I long for more stories like this.

I even buy his argument that hearing stories like these should be part of every American’s moral education — and unfortunately, is far too often not.

IT WAS BROOKS’ introduction that sold me on this book — as I stood in a sterile Barnes & Nobles Bookstore, three years after finding my way back to the high school classroom.

Like Dante in The Divine Comedy, Brooks found himself at the midpoint of his life in a dark forest, contemplating the emptiness in his life. He had found worldly success, had built a life that from the outside looked like the pinnacle of the American Dream (for a writer), but it was one that left him with the dry taste of ashes.

He needed something more. And so he began to research, began to look at the stories of other people who had faced his personal crisis. As he examined the stories of Dorothy Day, Ike Eisenhower, even St. Augustine — people who built a powerful reservoir of strength that helped them endure difficult times — Brooks discovered a pattern in their lives.

You have to go down in order to come back up.

Call it going out to the desert, pushing into the woods, taking a personal journey — each of these individuals developed character by going through difficult times, not by entering a safe space.

Only then could they find their vocation, the thing that gave their life meaning.

I WAS PARTICULARLY fascinated by the philosophy of moral values Brooks discovered. In fact, I didn’t even know it existed. It’s what Brooks calls the School of Crooked Timber.

It’s the belief that all of us are broken, that no timber is made straight, that life is intended to be a series of struggles and lessons — and that all of this builds moral fiber and strength of character.

Life is meant, Brooks argues, to be a series of battles with one’s self, battles that build straight character out of crooked building materials. Brooks’ role models are not perfect people. No, they are people who started out life with an imperfect substrate, and slowly, over a life dedicated to causes larger than themselves, straightened those timber beams into something worthy of their vocations.

As I listened to his stories told in hardboiled, journalistic fashion, time and time again, I found myself in tears.

I like almost all of his stories, but George Marshall might be my favorite. Time and time again, he was overlooked for the glory of battle, held back from being given a field commission when it might have brought him fame (or even the Presidency). Instead, he chose the low road, refusing to pressure President Roosevelt into choosing him for high visibility roles on the world stage.

When the President rightly judged that the nation needed Marshall in Washington D.C. — so he could remain at Roosevelt’s side and guide the military through logistics and tough personnel decisions — Marshall obliged, putting his own wishes aside. His hard, silent, behind-the-scenes work made it possible for the allies to win World War II.

Only the Marshall Plan — a reshaping of the world order — indelibly marked his name in the history books. In fact, Marshall was too humble to name the plan after his own name. Others did that for him out of sheer respect and admiration.

I wept as I listened to Brooks tell of Marshall’s death, when Prime Minister Churchill came to visit. Churchill stood there, viewing Marshall’s small, wasted body on a hospital bed, already in a coma. He stood there at the door, unable to comfort his dear friend. He stood there, weeping.

Churchill understood he was looking at greatness.

Again and again, I listened to Brooks’ stories of people who wrestled with their deepest failures, and I grasped in a new way what I’d never quite grasped before — that character is built while you travel the lowest places in your life, when you take the difficult road.

I thought about my own departure from the high school classroom almost a decade before, leaving a teaching position in Los Angeles, writing for HuffPost full-time at first, and then when a book deal failed to materialize, teaching evening school to support myself.

The way back into a high school career was difficult. It really took my fiance’s encouragement to believe that I might still love working with that age group.

But eventually I returned. Eventually, I was able to write about my departure. Eventually, I saw what a gift that time was away from my vocation.

Now, as I reflected on Brooks, I realized for the first time why I had needed to process that break with teaching that occurred almost a decade ago. I thought about my dark journey home to Ohio, the surprise healing that took place between my parents and me, even my stint with construction work.

It took time, reflection, and discussion with close friends to process what I had lost during two decades outside my Amish-Mennonite community. And when I was ready, I returned to the world, joining my true love in Seattle, where I’ve lived ever since.

You have to go down in order to come back up.

BROOKS DOESN’T HOLD to the idea that one should choose a vocation by looking deep inside one’s heart. Instead, he points back to the way people’s vocations were chosen.

They allowed life to choose it for them.

In other words, the community’s needs should determine your vocation, not your own needs.

This goes completely against our cultural emphasis today, what Brooks calls “The Big Me.”

I realized this time as I read it, that there has been a dual conflict within my own life. As a teacher, I’ve spent my life encouraging students to do exactly what our culture tells them to do — to determine what they love most, and go for it, no matter what obstacles they face.

I’m rethinking that, in part because I realize that I have spent my entire life following a different path.

This goes completely against our cultural emphasis today, what Brooks calls “The Big Me.”

I entered teaching because our conservative Mennonite community needed teachers. I learned servant leadership by practicing it. Somehow, they saw that I had potential in that area, and so I began teaching, starting college only after I left construction work, tried out teaching at a small parochial school, and then entered college specifically to become a trained teacher.

When I left my community, I tried other things, but kept returning to the craft that made me happiest — serving young people, preparing them to thrive in the world.

But I also learned from Brooks that I was wrong on why I should strive to become a better teacher. Not because my goal is to serve the community. That creates narcissistic obsession with other people’s likes.

Instead, Brooks argues, one should strive to achieve excellence. The craft is what should rule you. You are happiest when you know you are teaching well, not when your students and their parents praise you.

In this way, society has gotten it all wrong.

Becoming an excellent lawyer, artist, accountant— or even a teacher — means striving to master the daily skills of your vocation. It does not mean trying to gain “likes” from the community you serve. Character, as the old adage says, is formed when no one is looking.

And the character I now possess is not the character I will own in a decade. If I recognize the need for hard battles, if I allow them to develop sinews and muscles within my soul, that change will be for the better.

It took Brooks to help me understand this moral philosophy — this School of Crooked Timber. For this reason, Brooks is a true soul teacher.

I DIDN’T REALIZE any of this during my interview at that small Seattle school. I didn’t end up taking a job with them either. Instead, I began substitute teaching at a small, island school because their chemistry and physics teacher needed to attend his dying father.

I knew next to nothing about either subject. My wife claims that when they offered me the job, I called her and asked, “What’s physics?”

But I came to school every day and worked hard to learn how I could teach chemistry or physics. I made friends among my new colleagues. At the end of that year, I was offered a job coaching the debate team, along with a few Freshman English classes. I didn’t know anything about debate either, but I coached my students to the best of my ability.

Two years later, the school needed a journalism adviser, something in which I finally had some experience. I accepted the responsibility.

Eventually, through marriage and the daily routine of teaching, I escaped my midlife crisis. As I worked with students who attended my classes, as I practiced my craft, as I took on a more and more demanding schedule, I once again found meaning in my vocation.

I realized I was happy again.

Only this time — thanks to the right question, and an administrator who knew when to wait for my answer during a job interview— I knew why.

This was so inspiring I sent it to all my email and FB contacts.

Steven’s feature on David Brooks makes me think of several things:

“Character is destiny.” -attributed to Heraclitis That, to me, means that our character shapes what we become, what we become shapes our character.

I was trained as a high school English teacher, but four years into my career, declining student enrollment at our school and the possibility of cutting faculty (those with less seniority), inspired me to step up and offer to try my hand at teaching German, as well. My job was not in jeopardy, but I didn’t want to see my colleagues lose theirs. It was a challenge to stay one step ahead of my students as I worked to re-learn the grammar and vocabulary of a language I hadn’t studied in years, and I was always embarrassed whenever actual Germans would visit my classes, but my choice to teach German for twelve of my thirty-seven years of teaching opened up many rich opportunities for me in life.

That is what happened when English teacher Steven saw a need, willingly took a risk, and served for a season as chemistry/physics teacher Steven.